Sometimes your Angular application needs to be a little bit different depending on the environment. Maybe your local development build has some API services stubbed out. Or you have two production destinations with a little bit different behavior. Or you have some other build-time configuration or feature toggles.

The differences can be on any level: services, components, suites of ngrx/effects, or entire modules.

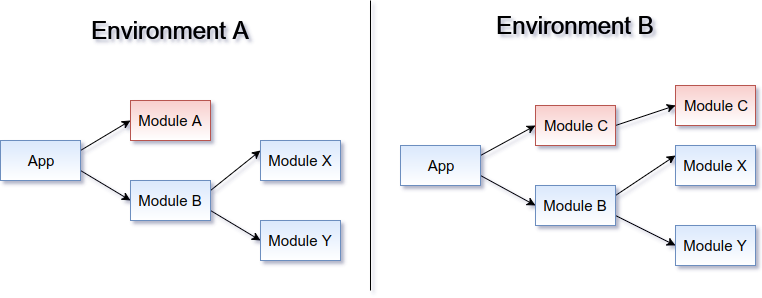

For example, it could look like this:

The dependency injection and module mechanism in Angular is pretty basic, and it does not seem to offer much to answer such use cases. If you want to use ahead-of-time (AOT) compilation (and you should!), you can’t just put random functions in module definition. I found a solution for doing it one service at a time, but it’s pretty ugly and not flexible enough. The problem does not at all seem uncommon to me, though, so I wanted to describe a nice little trick to work around this.

Sample app

Let’s study this on a sample app. To keep things interesting, let’s make a realistic simulator of various organization hierarchies.

We’ll need a component to tell us who rules the “organization”:

<h1>Who owns the place?</h1> {{(ruler | async).name}}!

@Component({ selector: 'app-root', templateUrl: './app.component.html', styles: [] }) export class AppComponent { ruler: Observable<Ruler>; constructor(rulers: RulersService) { this.ruler = rulers.ruler; } }

As well as a service:

export abstract class RulersService { abstract get ruler(): Observable<Ruler>; }

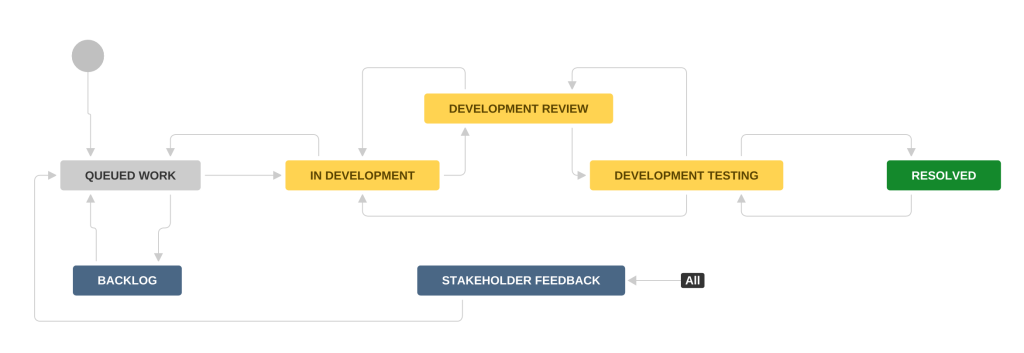

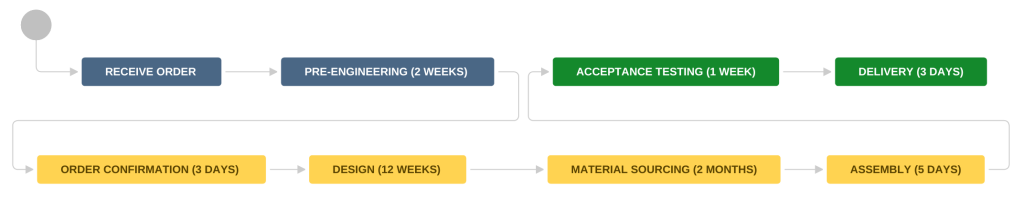

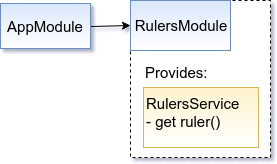

On a picture it could look like this:

Now, let’s say we have two environments:

- Playground, where little Steve would really like to own the place… except that he can only do that when the local bully is not around, and that’s only when he’s eating. To determine the ruler we need to ask the Bully’s mother about his status. So it goes.

- Wild West, where the rules are much simpler in comparison: It’s sheriff who runs the show, period.

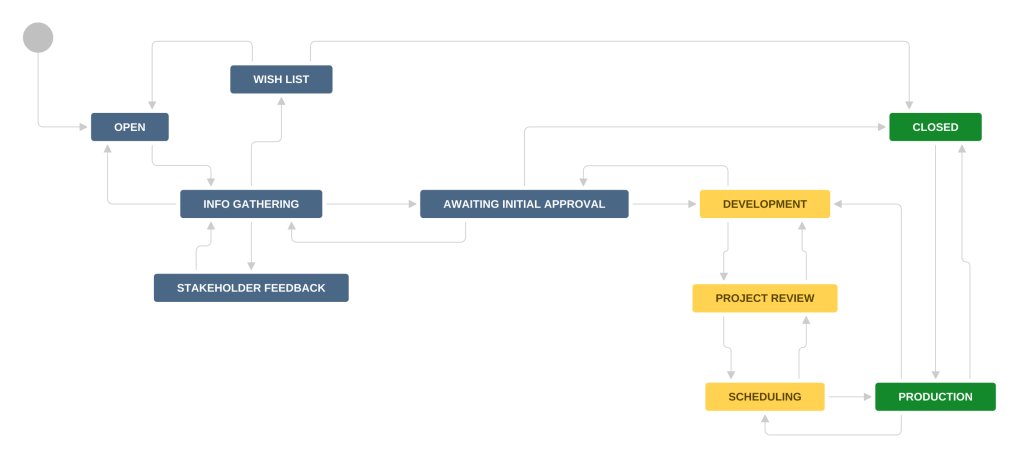

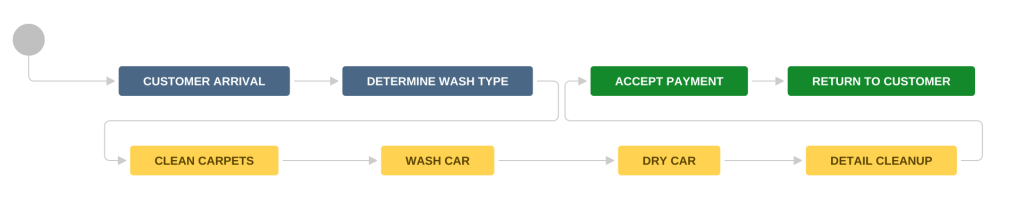

In other words, we need something like this:

So, how to achieve that?

Solution

The solution is actually pretty straightforward. All it takes is a little abuse (?) of Angular CLI environments. Long story short, this mechanism provides different environment file to the compiler based on a compile-time flag.

If you check the documentation or pretty much any existing examples, the environments are typically used to provide different configuration. Just a single object with a bunch of properties. You might be tempted to use it in some functions on module definition, but it’s not probably not going to work with AOT. Oops.

However, at the end of the day it’s just a simple file substitution. You can put whatever you like in the file, and as long as it compiles everything is going to be OK. Classes. Exports from other files. Anything.

In our case, the AppModule can import the RulersModule from the environment. It doesn’t care much what the module actually contains.

import { AppComponent } from './app.component'; import { RulersModule } from '../environments/environment'; @NgModule({ declarations: [ AppComponent ], imports: [ BrowserModule, RulersModule ], providers: [], bootstrap: [AppComponent] }) export class AppModule { }

The environments would export it from the relevant “package”. They could have the classes inline, but I prefer to keep them in separate files closer to the application.

export const environment = { production: true }; export { PlaygroundModule as RulersModule } from '../app/rulers/playground/playground.module';

export const environment = { production: true }; export { WildWestModule as RulersModule } from '../app/rulers/wild-west/wild-west.module';

Now, the modules:

import { RulersService } from '../rulers.service'; import { PlaygroundRulersService } from './playground-rulers.service'; import { BullysMotherService } from './bullys-mother.service'; @NgModule({ providers: [ BullysMotherService, { provide: RulersService, useClass: PlaygroundRulersService } ] }) export class PlaygroundModule { }

import { RulersService } from '../rulers.service'; import { WildWestRulersService } from './wild-west-rulers.service'; @NgModule({ providers: [{ provide: RulersService, useClass: WildWestRulersService }] }) export class WildWestModule { }

The final trick that makes these work is that there is an abstract class/interface for the RulersService, and AppComponent (or other services, if we had them) only depends on that. Actually, this pattern has been around for a while. This is the old good programming to interfaces.

The same goes for the RulersModule: In a sense it’s abstract too, AppModule doesn’t know or care what concrete class it is. As long as the symbol with the same name exists during compilation.

This sample demonstrates it on the module level, but you can use the same trick for any TypeScript code, be it a component, a service, etc.

I am not sure if such use of environments is ingenious, or insane and abusive. I have not seen this anywhere. However, it does solve a real problem that does not seem to have a solution in the Angular toolbox (and it’s not particularly toxic).

Sample app on GitHub

Check out this sample app at my GitHub repository.

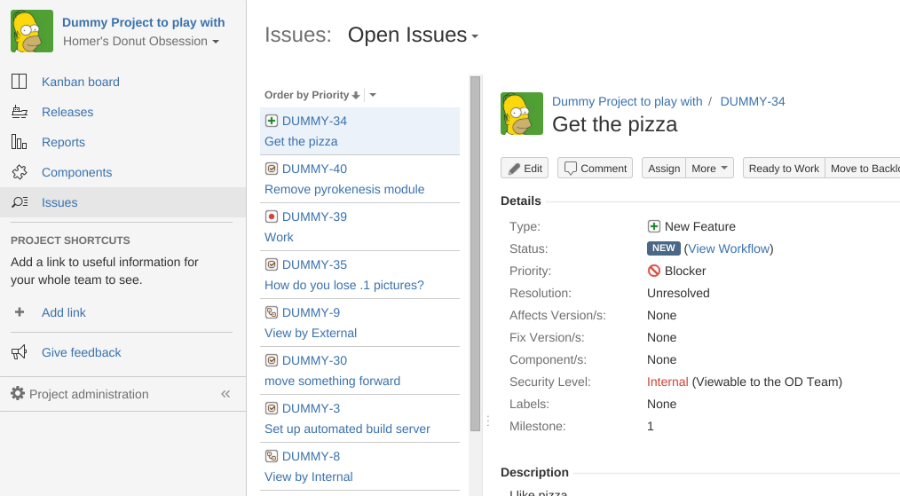

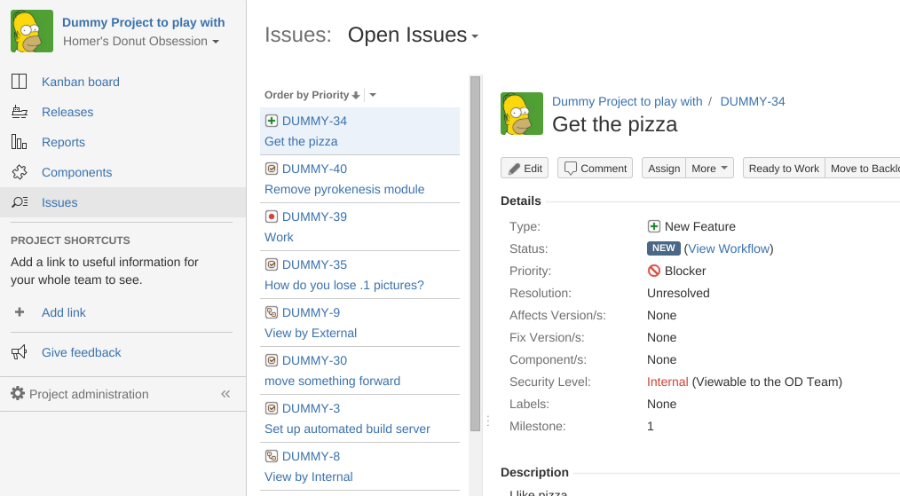

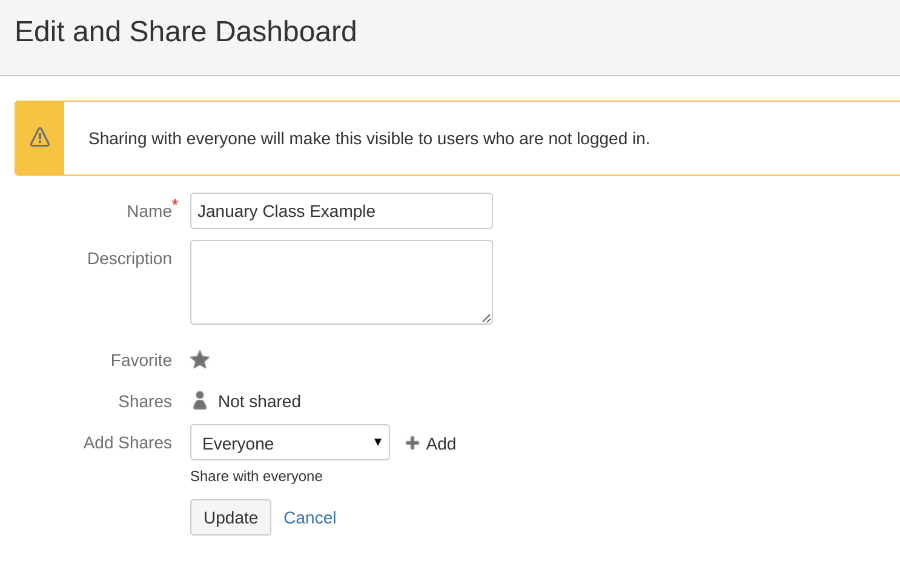

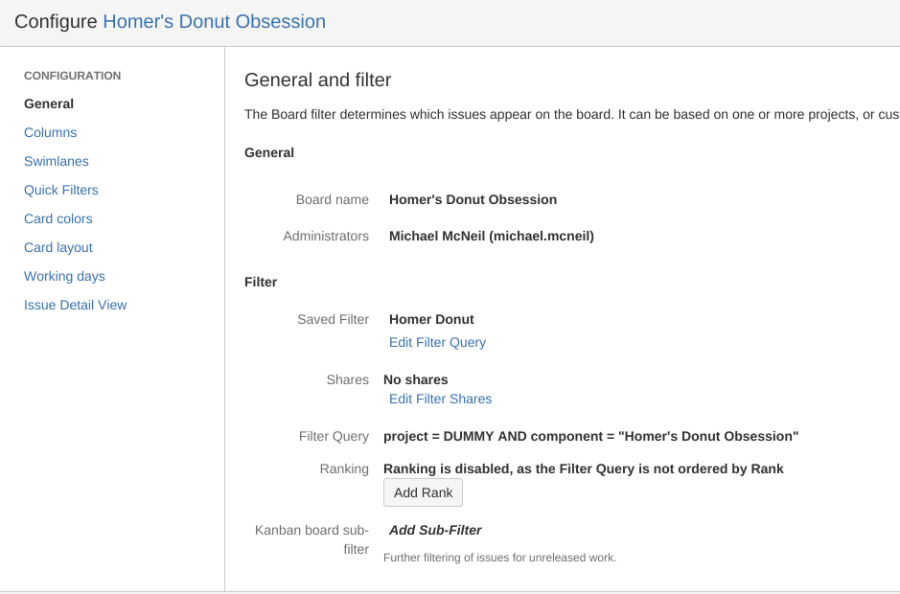

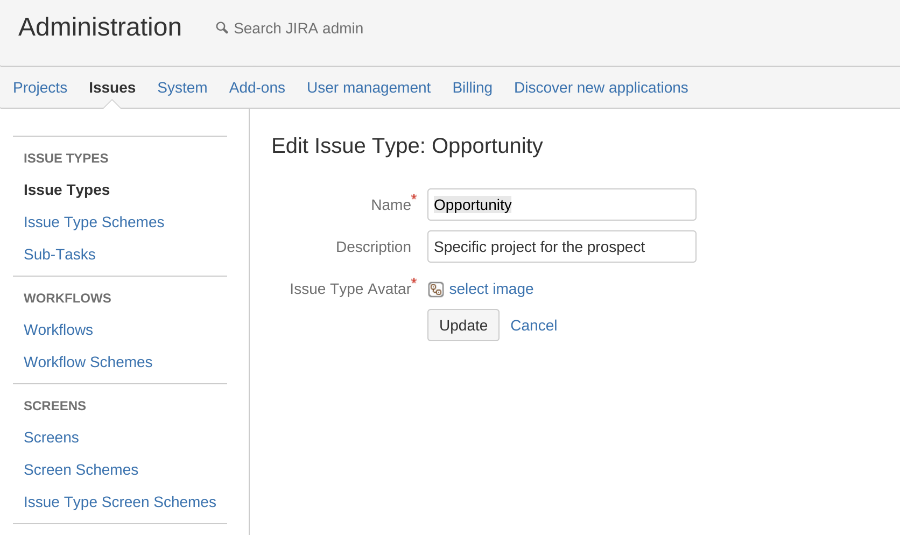

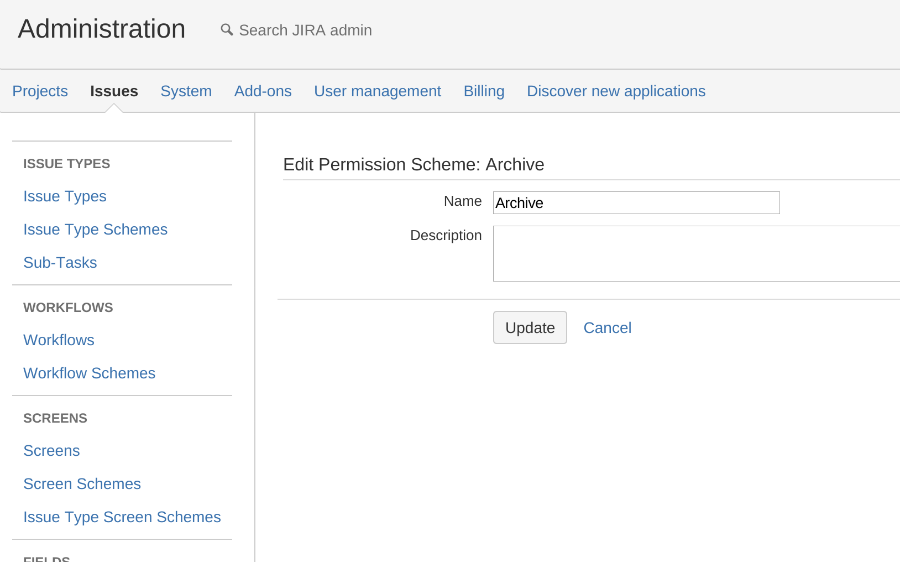

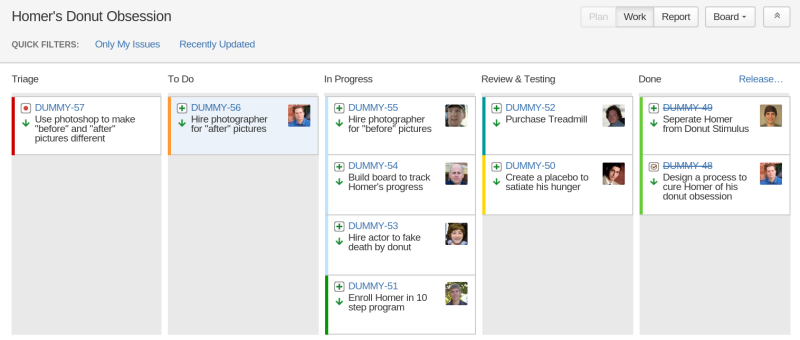

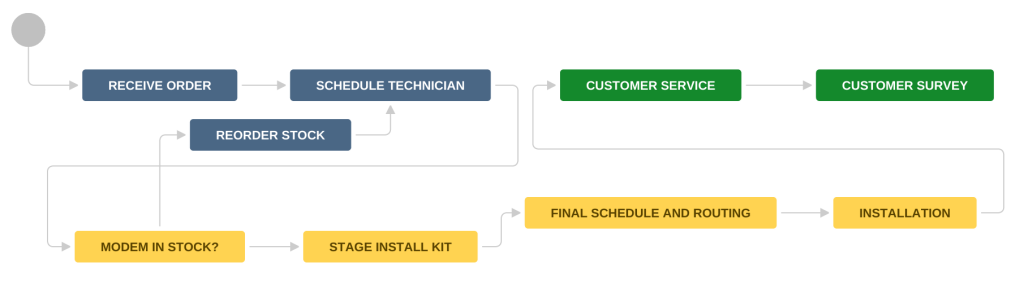

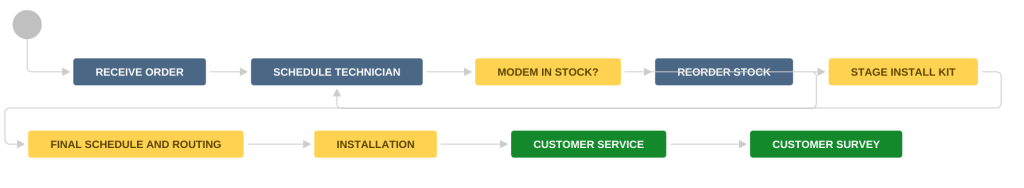

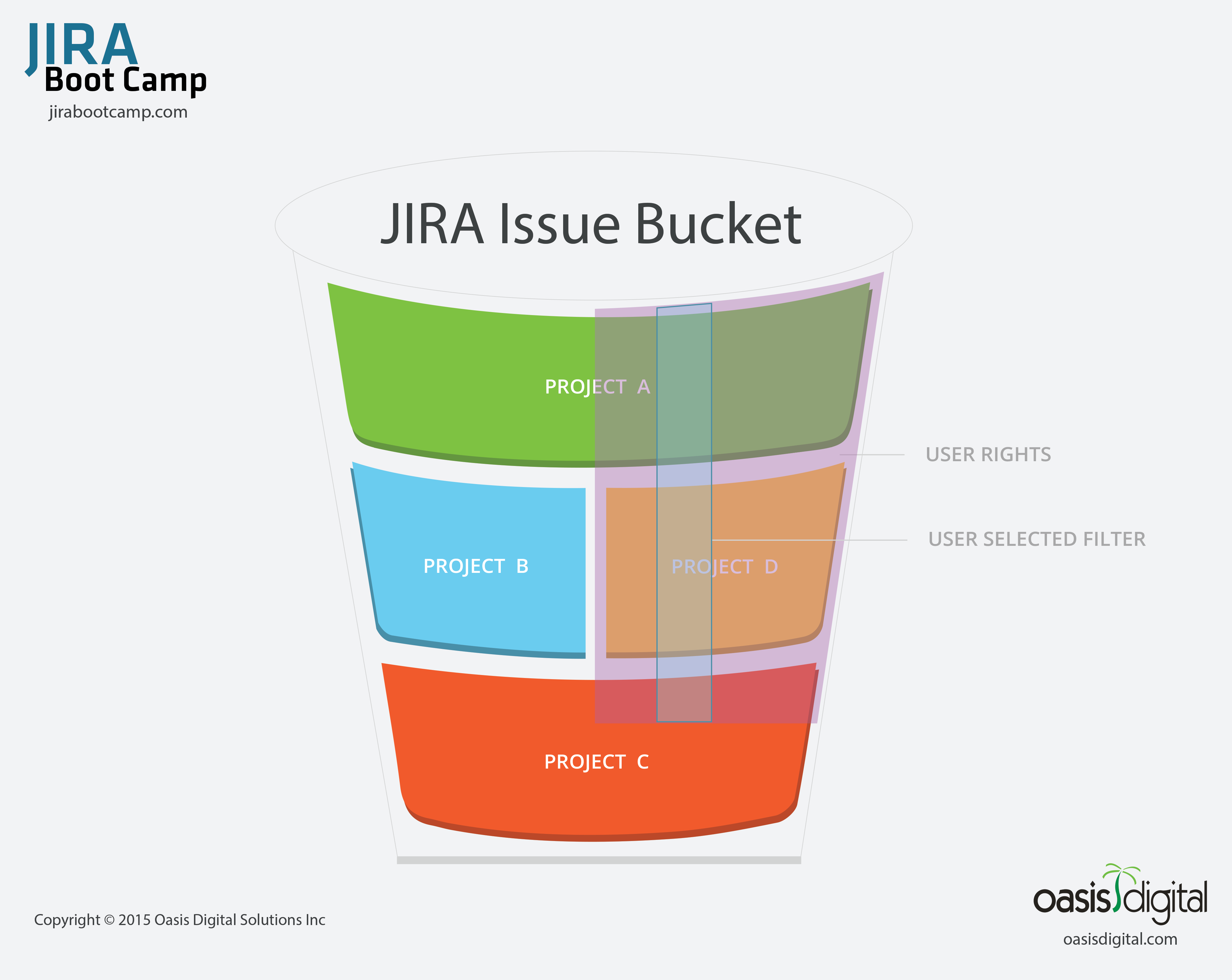

In every task within every job there is a context, and a certain set of information that is needed. System designers have learned to present the information the user needs at a particular point in the work process. There are many mechanisms in a JIRA workflow to assist with this. The most powerful is the idea of screens associated with transitions in a workflow.

In every task within every job there is a context, and a certain set of information that is needed. System designers have learned to present the information the user needs at a particular point in the work process. There are many mechanisms in a JIRA workflow to assist with this. The most powerful is the idea of screens associated with transitions in a workflow. Pride of authorship can be devastating to a system. Every organization is different, and your users matter. Listen to them and iterate on your workflows. Provide a mechanism, often another JIRA project, where users can make suggestions. Ask your users to critique screens and provide feedback about ways to improve their productivity.

Pride of authorship can be devastating to a system. Every organization is different, and your users matter. Listen to them and iterate on your workflows. Provide a mechanism, often another JIRA project, where users can make suggestions. Ask your users to critique screens and provide feedback about ways to improve their productivity.